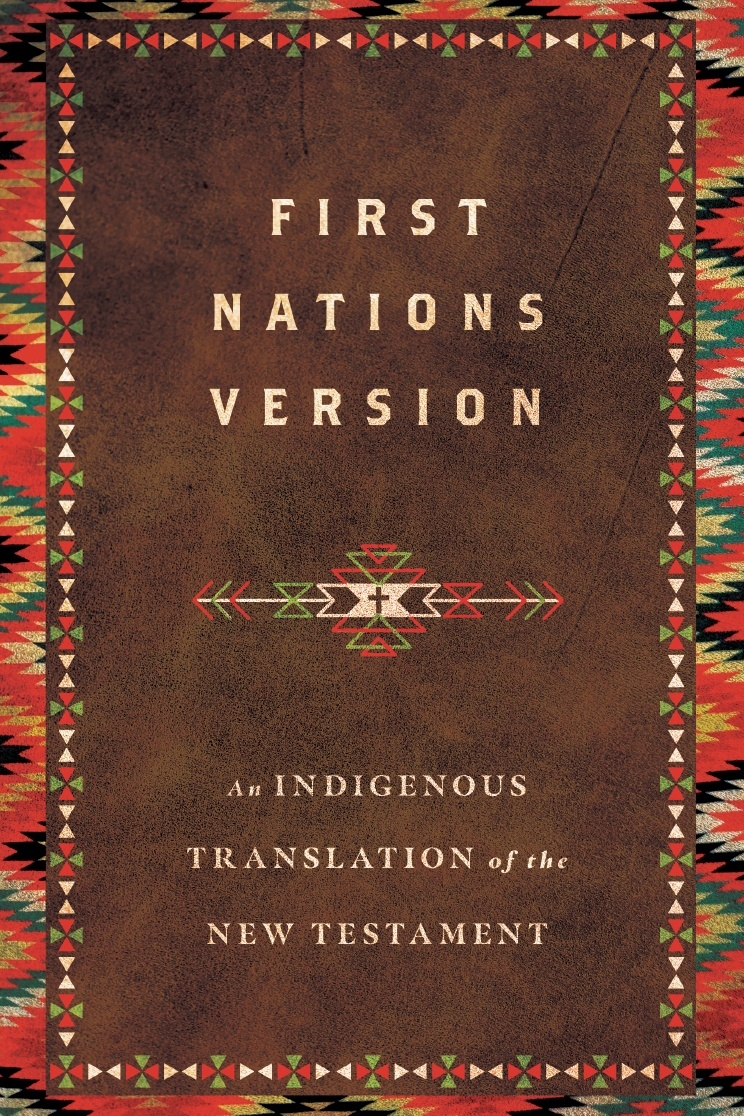

Terry Wildman on the Making of "First Nations Version," a New Indigenous Bible Translation

Years ago, Terry Wildman encountered a version of the New Testament in Hopi, but he could not find anyone who could read it. For so many Natives, understanding their own languages is a skill that has been lost because of colonization, yet reading the Bible in modern-day translations still leaves something to be desired. That experience planted a seed in Terry that eventually became the First Nations Version of the New Testament that reflects the oral storytelling of Native cultures. In this interview, you’ll learn about the collaboration between representatives from multiple Native tribes and better understand why certain words resonate more strongly for Native readers (or can even potentially cause trauma and need to be avoided).

Can you tell us the origin story of how you came to translate the First Nations Version?

Terry Wildman: As I began to learn about my Native heritage and visit places where Native people were, Creator called me out into the Arizona-New Mexico area, and I connected with a ministry up on the Apache Reservation. I was so surprised that there seemed to be extraordinarily little of the culture in the Native churches on the reservation. It was like the only thing Native about them seemed to be that some of them spoke their language. Then we got an invitation to pastor an American Baptist church, on the Hopi Indian Reservation, at a mission that was over 100 years old. It had been founded about 100 years earlier. I found myself living more closely among very traditional people, and I felt I had a lot to learn. But one thing I learned as the pastor was that we had a storage room in the fellowship hall. And in the storage room, I opened a box. I got curious, snoopy; you know? “What's in here?” Because we were reading the NIV (New International Version) Bibles in our churches. And we used to joke about it: NIV, "New Indian Version." Because so many of the Native churches were using the NIV Bible. But what happened was, I found a box of New Testaments translated into the Hopi language. And I was so excited. I thought, "Oh, man, I wonder how this translation works. I'll get somebody to read it for me."

I found a box of New Testaments translated into the Hopi language. And I was so excited. I thought, "Oh, man, I wonder how this translation works. I'll get somebody to read it for me." And that was an awakening right there. Because I discovered that no one could read it.

And that was an awakening right there. Because I discovered that no one could read it. No one in our church could read it. No one in other churches could read, I couldn't find anyone. And I discovered later the reason was that in the boarding schools, they never taught us, Hopi, they taught us English. They didn't teach us how to read these translated Bibles. Later, we found out that across Turtle Island, which we call North America, this was true. Most of our Native people cannot don't speak their language, let alone read their language. I talked to a traditional or, a friend who's a Native Navajo. And he told me that 1-2%, maybe 1%, could read the Bible in Navajo. That was the beginning of, wow, you know, this is eye-opening. And so, the seeds of an idea that we needed a translation in English began to germinate you know, be planted, I should say. They weren't germinating yet, but it was planted.

Can you give us a little insight into what it was like for you to work with a translation council to produce this version?

Wildman: So, what happened was the President and CEO at OneBrook Wayne Johnson, contacted us, and we agreed to work together. We began a partnership with this Canadian organization, which is a member of the Wycliffe Global Alliance of translators. They suggested that we put together a council. So, we decided on twelve Native people, and because Darlene and I had been traveling for years and years on the road, making relationships across this Turtle Island, North America, I knew a lot of people.

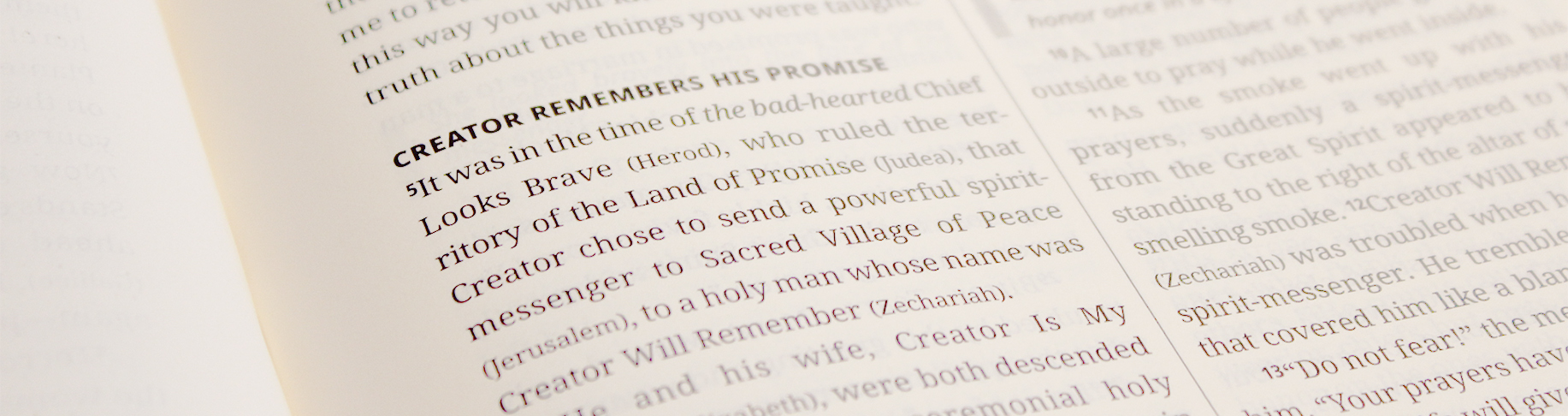

When we got the council involved, I had to submit all my work to the council. We had to work together and figure out how we were going to word things. And because there are so many different tribes and so many different tribal cultures, we had to figure out commonalities between all our tribal people and use some of the more common ways of speaking more traditionally, as the elders might speak. We went through over 100, almost 200, key terms, and we decided together, here's how we're going to say those in English. Here's how we're going to translate "kingdom." Here's how we're going to translate "sin." Here's how we're going to translate "priest,". It’s still in English, but here are the word choices we're going to use that relate to our Native people.

Can you give an example of some of that?

Wildman: Absolutely. One of the things that's happened because of the boarding school experiences and the church involvement in those boarding schools there are some words that trigger a defensiveness for Native people. And those words have to do with, for example, "church." So, we said, okay, we don't want to use the word "church." And besides, does anybody know what the word "church" means? Where did that word come from anyway, even in English? Does anybody know "c-h-u-r-c-h" it only has meaning because we grew up as believers knowing, that it wasn't the building, it's a gathering of people. People don't know that, and the word "church" has colonial baggage attached to that. So, instead, we decided on a relational term for this ecclesia, this gathering we're the called-out ones, we're being called out of the world into a family. So, we call the church the "sacred family," Creator's sacred family. And in the back of the translation, we have a glossary of why we translated a lot of these especially important words.

The reality of Christian publishing, and publishing more broadly, is that Native voices are still so underrepresented. Can you give us your thoughts on how the writing and publishing journey might be different for Native authors?

Wildman: You know, that's an amazing question. And I don't even know if I have the answer for you for that. I do know that a lot of Native people have a lot to share. And that our sharing has been undervalued within the body of Christ. And our culture has been undervalued. And so, I think what it will take to work with Native people, and Native authors is humility. It requires the dominant culture to say, "We don't know who you are; we are depending on you to tell us who you are. And we're not going to tell you how to do that. We're going to let you do it in the way that's most meaningful to you." And that's one thing I appreciated when InterVarsity Press decided to publish this. They assured me that they would not be trying to reword it for us, they would let us do the wording. They would only look at sentence structure, for any errors. And if they found anything, they would just ask questions, and let us make the decision. And that's exactly what happened.

This interview was excerpted from The Every Voice Now Podcast. Listen to the entire episode.

SPECIAL OFFER | Get 50% off the First Nations Version Limited Hardcover edition! Offer expires November 30, 2022.

Watch an IVP Exclusive Interview with Terry Wildman.